Geography of our Mountain Community

Hudson Ranch Road

A nearby drive into Early California

By Lynn Stafford with Liz and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Bill Buchroeder, Liz Buchroeder and Mary McDevitt

West of PMC, Mil Potrero Highway goes through a pine forest two miles up to a pass called Apache Saddle. After that, the road straight ahead becomes Hudson Ranch Road (HRR). The road is named after early local ranchers. Many folks drive that road to go to Taft or the coast. This is a winding, narrow back road that descends more than 3000 feet in a little more than 20 miles.

A leisurely drive on HRR with several stops can be a destination in itself. It is a close-by view of what much of California was before the boom of modern human civilization hit this state. The land beside the road is either National Forest, private ranch land or Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge. The latter two ownerships do not allow visitors. Since it is often hard to know who owns which land, the best way to become familiar with the country is to drive slowly and look for safe pull-outs. The key to enjoying this area is to slow down. Take a snack and drinks, maybe a pair of binoculars and definitely a camera. Since some people insist on driving too fast, stay safely off the road. There are several places to pull fully off the road. Be careful not to park on vegetation. Wildfire can start easily. Do not across any fences.

Figure 1 and Figure 2

By the time you read this, it will be spring, a great time of year for a leisurely drive with many stops. HRR passes through several life zones. Up at Apache Saddle, at 6,100 feet, one can find Jeffrey pines. Then one passes through dense thickets of scrub oak, pinyon pine and juniper (Fig. 1). Finally, the brush tangles give way to grasslands with cattle and horses down to Highway 33/166 at 2,900 feet (Fig. 2).

Figure 3 and Figure 4

During spring and early summer, the grass greens up. Early flowers include fiddlenecks (Fig. 3), lupine (Fig. 4) and poppies (Fig. 5). Later on, the beautiful and aptly named Farewell-to-Spring covers some hillsides (Fig. 6). Careful scanning of the rolling land might reveal a coyote or even tule elk. There are birds of prey all year, soaring high or sitting on utility poles. Red-tailed hawks (Fig. 7) and American kestrels are the most common to see, but others, including the California condor (Fig. 8) are also possible to spot. Bitter Creek Refuge was created specifically to aid in the reintroduction of condors. Meadowlarks, horned larks, loggerhead shrikes (Fig. 9) and various sparrows and finches can be found along the fence lines.

Figure 5 and Figure 6

A few precautions for a relaxing drive are appropriate. One, there are no services of any kind. Cell phone coverage may be questionable. Weather can be an issue. I have had to deal with snow, ice and extremely thick fog, none of which is fun on a narrow winding mountain road. Check weather and road conditions carefully. There are at least three potential things to watch for on the road that need to be avoided. In a couple locations, rocks can tumble down onto the roadway, especially after rains. In the spring and early summer, snakes often across the road. Please do not hurt these valuable members of our wildlands. In the fall, occasionally, there is another wildlife movement. Male tarantulas are on the prowl for females. My wife, Edie, used to carry a magazine to let the spider crawl onto, then escort it across the road.

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9

One last item to mention is that there is a small primitive Forest Service campground, Valle Vista, about halfway along HRR. It provides an incredible view of the San Joaquin Valley, and makes a pleasant lunch stop. The dirt road leading into the camp is narrow, steep and easy to miss. If our local world of nature interests you, do take time to leisurely enjoy this country.

--------------------------------------

Mil Potrero Wetlands

By Lynn Stafford with Liz and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Bill Buchroeder, Charlie Hall, Liz Buchroeder, Lynn Stafford and Randy Cushman

We have a very unique and special resident here in PMC. It has probably been here for thousands of years. And there is not another one like it for close to 100 miles from here.

This is not a person, not an animal or even a plant. This is an ecosystem -- the Mil Potrero Wetlands. Several of our green belts contain portions of this unique ecosystem. The easiest way to see it is to drive along Mil Potrero Highway between Woodland Drive and Nesthorn Way. This time of year, it does not look like much; in fact, it looks like a dirty mess of dried brown vegetation.

Figures 1 and 2

Some folks worry this might start a wildfire. However, the truth is, this would be the last type of vegetation in our community to burn. Some of the dead material visible are stems of last year’s virgin’s bower (Clematis), a vine that grows over woody bushes (Fig. 1). In this area next to Mil Potrero Highway, it has clambered over wild rose, choke cherry and willows (Fig. 2). All of these bushes look dead now in the winter. They are very much alive, and their stems are green inside. Within a few months, this whole plot of well-watered vegetation will be vibrant with green and other colors.

Figures 3 and 4

These wetlands consist of four basic types of habitat. There are running small streams (Fig. 3), wet meadows dominated by rushes (Figures 4 & 5), thickets of Arroyo willow, wild rose and other bushes (Fig. 6) and a few patches of riparian woodlands including red willow and Fremont cottonwood (Fig. 7). Before the development of PMC starting in the early 1970s, cattle grazing occurred in the meadows. Ernest Twisselmann, author of the Flora of Kern County, 1967, wrote “...prolonged heavy grazing has greatly accelerated natural erosion processes and the meadows are being rapidly cut through with ditches that are draining the subsurface moisture and changing the wet cienegas to dry meadows [and leading to] a deep dry canyon bottom.”

Figures 5 and 6

The building of PMC had two profound effects on the wetlands. A small portion of the wetlands was drained and filled to build the golf course and the Clubhouse. Grazing in the wetlands was halted. So, a small portion of the wetlands was converted to other uses, and the majority was, and is, being allowed to recover and flourish. In California, approximately 95% of the State’s wetlands have been degraded or destroyed. Wetlands are now protected by State and Federal laws. The PMCPOA is doing an excellent job of protecting our rather special and unique wetlands.

Figures 7 and 8

There are small bits of wetland vegetation, often called cienegas, throughout the mountains of Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties and the Tehachapi Mountains. But there is no equivalent in size or biodiversity of our Mil Potrero wetlands. Potrero is a Spanish word meaning pasture; it is also used to describe certain mountain elevated meadows. Mil can mean one thousand in Spanish, but the more likely origin of the word used here is a shortened form of mill. There has been logging in the vicinity of PMC in the past, and we have Sawmill Peak as a tribute to that history.

The wetlands of PMC are divided into three distinct regions. One region is the section visible on the north side of Mil Potrero Highway between Fern’s Lake and the lower end of Nesthorn Way. That section is one mile long and never more than 400 feet wide. It can be accessed on foot from the dirt fire road at Fern’s Lake next to the archery range that heads down the canyon towards Nesthorn Drive. It is a great walk from Fern’s Lake, but one must remember it is uphill coming back, and can get quite hot in the summer. As one walks downhill, the wetlands are on the right.

A second region is a scattered group of narrow wetlands in the Woodland Drive and Bernina Drive sections of PMC. The best access on foot is on the Water Company service road beginning on Mil Potero Highway (near Woodland Drive intersection) and ending at Freeman Drive. A portion of it is the so-called Snowflake Trail. It is a very pleasant walk, covering almost one mile each way, but climbing 400 feet.

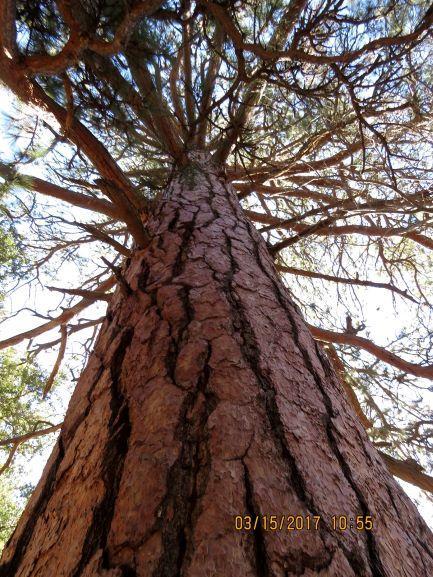

The third wetland region in PMC is the least visited and most difficult to access. Many residents may not even realize it exists. This wetland is in the eastern portion of PMC. It begins near the intersection of Mil Potrero Highway and Voltaire Drive and proceeds eastward beyond Yellowstone Drive. It is north and below Mil Potrero Highway, and is out-of-sight from the road. This is the location of the Jim Whitener ponderosa pine, our largest, and probably, oldest tree (400 years+) in PMC (Fig. 8). There is no developed trail to this region.

Figures 9 and 10

The Mil Potrero Wetlands have their own diversity of plants, and are visited by much of our wildlife. I see bear and deer scat frequently on my jaunts. Spring and summer, when the willows are popping out with catkins and leaves, the yerba santa (Lizard’s Tail) is blooming and the large deer grass clumps are greening out, are excellent seasons to visit (Figures 9 & 10). One may also find small orchids, blue asters and goldenrod. Many bird species can be heard and seen. This precious wetland jewel is completely within PMC property, and is currently being well protected within our green belts.

--------------------------------------

Mt. Pinos: A Special Place

By Lynn Stafford with Liz and Bill Buchroeder

Photos by Bill Buchroeder, Liz Buchroeder, Mary McDevitt, Lynn Stafford and Randy Cushman

We live on the north slope of a very unique and special mountain -- Mt. Pinos. At 8,847 feet, it is the highest mountain for many miles around. One has to travel 85 miles southeast into the eastern San Gabriel Mountains to find higher peaks. In the southern Sierra Nevada, it would be a trip of 95 miles to find a higher mountain. And in the California Coastal Range, the nearest taller mountain is Mt. Eddy near Mt. Shasta, more than 450 miles distant. Here, one can easily drive from Bakersfield in the Central Valley to high mountain forests (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Mt. Pinos is actually a ridge running mostly east to west. Mt. Pinos itself is the easternmost high point, then comes Sawmill Peak, Grouse Mountain and Cerro Noroeste. The isolation of this mountain massive has produced a phenomenon known as a biogeographic island. Populations of plants and animals have been isolated so long that some of them have begun to differ genetically. Merriam chipmunks are very common little rodents in PMC. But, up on the highest ridges, lives a different chipmunk, the Mt. Pinos chipmunk (Fig. 2). It prefers rugged high-altitude pine and fir forests with abundant fallen logs (Fig. 3). There are several other high-mountain animals that are isolated, including Clark’s nutcracker (a member of the jay/crow family) and the blue grouse (which is on the verge of local extinction).

Figures 2 and 3

There also are several isolated plant species, including a timberline pine called limber pine. One has to drive to the upper end of Mt. Pinos Road, then hike up a trail towards the top of Mt. Pinos, before encountering this five-needled pine at about 8,700 feet in elevation. These mountain species of plants and animals are probably stranded populations of a much more widespread mountain flora and fauna that existed several thousands of years ago after the last ice age.

Figures 4 and 5

Several unusual habitats have developed within our mountain. Up near the end of Mt. Pinos Road is a fine iris meadow (Fig. 4 and 5), otherwise unknown on our local mountain. Here in PMC, our water supply is entirely local, coming off the north slopes, mostly as snow. Other areas of western United States are very concerned about the present drought. Their water often comes from very distance sources, as much as 750 miles away. Our water is all local, and we are the only town in our watershed. So, by controlling our water usage, we can preserve our supply. The downward flow and seepage of water has produced the Mil Potrero Wetlands (Fig. 6), a highly unusual feature in Southern California mountains. This wetland lies completely within PMC. In addition to our more common tree species, there are a few isolated pockets of other types that are probably left over from cooler, wetter times. These include Ponderosa pine, sugar pine, big-cone Douglas-fir (Fig. 7) and incense cedar.

Figures 6 and 7

Our mountain features altitude-related seasonal differences. One can find wild flowers blooming in Antelope Valley and Carrizo Plains in March and April, while there is still snow up on the peaks. Summer does not come until July and August up above.

One of the important features of our Mt. Pinos is the absence of dark sky pollution. Modern humans, especially those who reside in cities, do not see the night sky. Light pollution of the night sky by modern human activity has been well documented. I have a 13-year-old grandson who has probably never seen stars. I, in PMC, am able to watch the Milky Way, notice which object comes out first at night and am able to observe the rotation of stars around Polaris (the North Star). Amateur astronomers gather at the parking area at the upper end of Mt. Pinos Road many times each year to observe the visible universe. This is one of their most important destinations in southern California. And it is part of the legacy of our mountains.

Figure 8

Mt. Pinos has a fascinating human history. The mountain has long been considered a sacred place to the Chumash. The trail to the peak has been named in honor of one Chumash elder, Vincent Tumamait (Fig. 8). The Ridge Route Communities Historical Museum in Frazier Park features local history with exhibits and special events and tours. The museum also sells maps and books.

Now is a good time of year to visit the tops of our mountains. Mt. Pinos Road ascends from the “Y” to the east of PMC. And to the west of PMC, at the pass known as Apache Saddle, Cerro Noroeste Road goes to the top of the mountain of the same name. Enjoy our mountains, but do be alert for summer thunder and lightning storms.